- Home

- Kat Richardson

Seawitch g-7 Page 7

Seawitch g-7 Read online

Page 7

“Yup. And then I had to show him.”

Quinton snorted. “I’ll bet he loved that.”

“About as much as you’d expect.” I peeled off the last of my wet clothes and wrapped the towel around myself.

“Hey, you don’t have to cover up for my sake,” Quinton objected, smiling.

“I’m cold.”

His smile widened into a wicked grin. “I can tell.” He walked over and wrapped his arms around me, putting the ferret on my shoulder as he started to kiss and nibble at my opposite ear. “I can warm you up. . . .”

I laughed and tried to wiggle loose. “Silly man. Dinner first.”

Suddenly Quinton twitched backward. “Ugh! Ferret tastes disgusting!”

Chaos made a leap for the kitchen counter as I started laughing. “You’re the one who put her there!”

“I hadn’t considered that she’d stick her tail in my mouth,” he added, making a face and turning toward the sink in search of water to rinse from his mouth the taste of ferret fur.

I chuckled and caught the fuzzy miscreant so I could return her to the floor where she belonged. Not that I hadn’t enjoyed the kissing, but I was still wound up from the long day and once we got to the sexual gymnastics I wanted to do more with Quinton than rush through a quickie on the kitchen counter. I took his distraction as an opportunity to slip away to a quick shower and some dry sweats.

When I returned, Quinton was pulling things out of the fridge. Neither of us was much of a cook, but Quinton at least had the skill of recognizing what bits and pieces might go well together. I’m strictly a prepackaged dinner girl and if I tried to put a dish together from leftovers, we’d end up dining on something like cream of beet on toast. I like food well enough; I’m just lousy at making it. On the other hand, I have never put things in the microwave that don’t really belong there.

Later, when we were sitting on the couch with dinner in front of us and Chaos was occupied with reorganizing her stash of toys, I recapped my day to Quinton at his request. I told him about the Seawitch and her missing passengers, my first soaking of the day, Linda Starrett, and then our conversation with Captain John Reeve.

“What worries me,” I said, “is that I don’t know if whatever was watching was there to begin with or if it was summoned in some way.”

“You mean because of the spell thing in the fountain or because he called it in some way?”

I gave a half shrug. “I’m not quite sure. That is, I’m not sure about the connection or if there is one or if he somehow conjured the thing into existence.”

“I’m not quite following you. . . .”

“First, I’m not sure what it was that I saw. It could have been what he was describing—a large doglike thing—or it may just have been something that size and I filled in the idea of a dog thing myself.”

“Does it actually matter?” Quinton asked.

“It may. If I could figure out what the creature was, I might be able to get a line on what powers are involved here and if it’s one of those creatures that is attracted by its name or if it’s something that can be tethered or . . . what. Most of what I’ve seen so far is pretty foreign to me except for basic principles. It all seems to be about water, which I haven’t had much experience with up till now.”

“Except for up at the lake last year.”

“Yes, but that was freshwater and it didn’t feel like this. The water was just a carrier of magic in that case, but here . . . it’s like the seawater or the sea itself is a power of its own. And I’m not ignoring the fact that there’s blood magic involved and that blood is also salty. I’m not quite getting a handle on this.”

“Well, you are dealing with sailors and boats and there’s a lot of tradition and superstition there. If, as you’ve said, this stuff is influenced by the things people close to it think and feel and fear . . . then that’s a lot of influence and shaping over a very long period of time. And not all of it will be homogenous. You could have more than one tradition in the mix on this coast. I mean, we have everything from English legends to the local Indian lore and the Viking myths that came over with Leif Eriksson.”

I gave that a moment’s thought and nodded. “True. Could very well be any or all of them. Or maybe I’m just a little thrown off by working with Solis. He’s kind of hard to read. Even when he’s freaked-out.”

“That’s what makes him a good cop. You’re not easy to read, either, you know. Most people find you a little . . . aloof.”

I raised an eyebrow and looked askance at him, feeling a bit prickly. “Aloof? Doesn’t that imply dislike?”

“Not from me, but you can understand how your tendency to keep your distance may look like distaste or disdain to some people. I know it’s part of the job—you need to keep your thoughts to yourself and not become a factor of your cases—but it does put you in the position of disinterested observer and that unsettles some people. They don’t separate their observations from their emotions and they don’t really understand someone who does.”

“Do you speak from experience, O Wise Sage?”

“Yup. My dad’s one of those guys.” His aura gave a brief, panicked flash of red before he shut his emotion back down, but I still felt it. “He makes you look like a passionately impetuous mayfly. I don’t think I ever saw him smile spontaneously in my life. Now, that is aloof.”

“I can honestly say Solis is not that chilly. I might be able to like him if he’d just crack the ice a little. . . .”

Quinton snorted. I cut him a narrow look as he said, “Oh yes, Ms. Pot. Meet Detective Kettle.”

“All right,” I said on an aggravated sigh. “I admit I’m a hard shell. But I did try to let him in.”

“Yeah, but what you let him in on is not an easy thing to get your brain around. Give him some time. You guys have to work together on this and he’ll either get it or he won’t. You can’t force him.”

“Yeah, yeah, yeah,” I groused, dismissing the problem for the moment, though I knew it was going to come back on me later.

Quinton just gave me a doe-eyed look and raised his eyebrows. I frowned back at him. I could feel something wasn’t right. The strange and tenuous magical connection between us vibrated like a drawn string and I didn’t know what he was concealing from me, but there was something. . . . I’m curious by nature and I wanted to pick and poke at this hidden thing until he told me what it was, but my better instinct said I shouldn’t.

I took a long breath and decided to redirect the subject back to the problem of whatever I’d seen in the Grey at Reeve’s house. “Maybe I should drop an e-mail to the Danzigers and see if they know what Reeve was talking about and if what I saw is the same thing.”

Quinton shook his head. “Mara and Ben are in Europe, working on his book,” he reminded me with a small frown of annoyance. “They’re not exactly glued to the Internet, waiting for you to cry for help.”

“I’m not crying for help,” I objected.

“Yes, you are, and you need to stop that.”

“Excuse me?”

He sighed. “Harper, I know you don’t want to hear this, but you’ve gotten lazy about doing your own research—which is ironic, considering that’s essentially what you get paid to do. They’ve been gone most of a year already and you still send queries to Ben and Mara as if they have nothing better to do than answer your questions about magic. And, yes, yes, I do know they’re a great resource,” he added, putting his hands up to stop my objections. “And there’s no one out here half as useful, but that’s just the problem: You can’t use your friends that way.”

I gaped at him. “I don’t.”

“Yes, you do. And most of the time it’s all right—we don’t mind. But you said it yourself: You have to stop taking your friends for granted. I know you can manage to get through this stuff without treating people like resources.”

I felt stung and didn’t know what to say to that; at the same time I had the feeling there was more behind Quinton’s concern than he was say

ing. It was true that I tended to rely on my small circle of friends too much and, frankly, to put them in situations that weren’t always safe or comfortable because I needed something and I hadn’t weighed the possibility that they wouldn’t want to or might get hurt by helping me. And because I have an unnatural gift for persuasion, they didn’t tell me no when they probably should have. I looked down, suddenly uncomfortable. “I guess I’m a hard friend to have,” I muttered. “Or maybe . . . I just don’t know how to be a friend.”

Quinton wrapped one arm around my shoulders and pulled me tight against his side. “That is not true and I’m not trying to make you feel bad. I’m just reminding you—as you’ve said you wanted—that you need to think about these things before you presume on friendships. Ben and Mara and I would all walk across burning coals for you, but you shouldn’t assume that we don’t mind.”

I bit my lip hard. I didn’t like being reminded of all the ways I’d abused my friends, but while Quinton was only doing as I’d asked—kicking me in the conscience where I tended to have a blind spot—it was pissing me off. I can be a jerk—I’m not saying I can’t—but I wasn’t thrilled by being reminded of it. Especially when I had the increasingly strong feeling there was something he didn’t want to tell me and this conversation was at least partially a dodge to avoid it.

I took a few more long slow breaths and unlocked my jaw. “I’m not saying you shouldn’t remind me how to be a better friend, but maybe we should put further discussion of this off for now,” I suggested.

He looked hard at me, as if he were searching for a sign in my face that I apparently wasn’t giving. “All right,” he said at last. “But I don’t want to leave it like this.”

I shook my head in confusion. “Leave what?”

“No. I mean ‘leave’ as in actually go away: I have to go back out. I just wanted to . . . see you before I did.”

I frowned at him. “What’s wrong? Where do you have to go?”

“It’s just more work stuff. I have to do it.”

“Work stuff? Like with the three-letter acronyms?”

He made an uncomfortable shrug.

“I thought you were done with that.”

“Me, too,” he said, his voice rueful as he glanced away from me.

I wanted to ask a half-a-hundred questions, but I stifled them and we spent the next quarter hour trying to pretend we both weren’t uncomfortable and lying about it.

Finally I gave up. “Does this have an end?” I asked.

He squeezed his eyes shut and gave a tiny shake of his head. “I don’t know.” He stood up and took the plates out to the kitchen to keep the ferret from helping herself and, I guessed, to avoid making more of a reply.

I caught him before he could slip out the door. “Are you coming back?”

“Yeah. Just trust me.”

“I do.” I wanted to ask why he didn’t trust me, but I knew that would be a big, fat mistake. So I shut my mouth, which made our parting kiss a cold, narrow, and unsatisfying thing.

As soon as the door was closed behind him I wanted to scream in frustration. I was trying to be a better friend, even to my lover, to give as well as take, and here was something I could do nothing about. I couldn’t complain, I couldn’t remonstrate, I couldn’t even be sure what the problem was, though I’d have put money on the chance it was something to do with his mysterious family, since he’d been more forthcoming about having worked for the government than he was about them.

I growled and threw the nearest object: a coffee mug that shattered against the doorframe.

Broken ceramic showered down onto the floor and the ferret scampered to it, hopping in fury.

I watched her a moment, fuming, until her antics worked past my annoyance and left me shaking my head in self-disgust.

“That was a stupid thing to do,” I chided myself, fetching the dustpan and broom from the kitchen.

I went to clean up the mess, having to field the ferret away from the sharp bits of former mug. And afterward I sent an e-mail to Mara and Ben, anyhow.

* * *

There are few things more emotionally terrible than interviewing family members of missing persons presumed dead for twenty-seven years. When someone’s been missing for a short time, the family usually has strong ideas about whether they are dead or alive and what may have happened to them. They will even argue with one another and with the interviewer about it. But when someone’s been gone without word or trace for so long, the sadness and confusion settles in and some of these people who can otherwise manage their daily lives become painfully disconnected when they talk about the missing. Time seems to flutter around them, shifting the phase of their reference from now to then to . . . some strange, unspecified time that is neither future nor past.

Gary Fielding’s family was in Portland, so Solis and I had chosen to leave them aside unless necessary and started with the family of Janice Prince—one of the two women who’d been listed with the passengers. But we hadn’t made a lot of headway with the Princes. Janice’s mother, now in her early seventies, kept breaking into tears. Her father was stony, glowering at us and offering nothing but negative comments such as, “I always knew it. I knew she was a bad one,” which threw Mrs. Prince into fits of crying and arguing against him. Mrs. Prince countered with, “No, Janice wasn’t bad! She was confused, poor thing. She just—she just didn’t fit in!” and similar statements, when she could make one at all between bouts of upset and tears.

The conversation went in circles of blame and recrimination that broke down into Mrs. Prince sobbing about what a good girl her daughter had tried to be while her husband just shook his head in judgment.

“She couldn’t help falling in with that fast crowd down at the marina,” Mrs. Prince cried to me. “They were so—they seemed so charmed.”

“Boat trash,” her husband muttered.

Mrs. Prince gave him a pleading look. “They were so glamorous. Even the ones without any money always seemed to be going wonderful places and doing exciting things! How could a little girl like our Janice not fall for that? There weren’t bad people. They weren’t! They were just—”

“Trash!” Mr. Prince spat.

“No, they weren’t. Besides, Janice worked there. How could she avoid them?”

“Excuse me, Mrs. Prince,” I interrupted. “Your daughter worked at the marina?”

She turned her reddened eyes to me. “Yes . . .”

“What did she do there?”

“She . . . she worked in the convenience store at the end of the fuel dock.”

“So she knew a lot of the regulars?”

“Oh yes! Janice would have such interesting stories when she came home! Who was going to Mexico or Alaska or out to the islands or taking their boat out for repairs. It was like all of them were her personal friends!”

“Was she particular friends with anyone?”

“Oh . . . I don’t know. I suppose. I don’t remember names now. . . .”

“Did she have other friends around the marina—other workers or anything like that?”

“Well, she and Ruthie Ireland spent a lot of time together. . . .”

“How did she know Ruthie?”

“Just from the marina.”

“More trash,” Mr. Prince declared. “Loose!”

“Now, dear, that’s not fair.”

“Sluts, the both of them,” Mr. Prince declared. “Better off dead and gone.”

Mrs. Prince broke into wailing sobs for the third or fourth time. I eyed Solis and wondered if we could just call this one done and go on to the next sad family on the list. He glanced back and shook his head in resignation. Then he got to his feet.

“Mrs. Prince, Mr. Prince,” he started. “We apologize for bringing up such painful memories. You’ve been very helpful.”

Mrs. Prince grabbed for his hand and turned her face up to his. She hiccupped and gulped as she asked, “Will you be able to tell us what happened to our little girl?”

“We hope so, Mrs. Prince.”

She let go of his hand reluctantly and covered her face with the tear-soaked handkerchief she clutched in her hands.

Mr. Prince saw us out, still hard, still disapproving. He opened the door and held it for us, scowling. He didn’t say anything as we left.

I walked behind Solis to his car—a blue Honda sedan so bland it would disappear in a bowl of oatmeal. Beside the car, Solis reached into his jacket and brought out his cell phone. It was one of those big-screened smartphones blinking with little messages and clever applications. He poked it a few times and smiled. “Our manuscript technician has had some luck. He should have some legible pages photographed for us within an hour,” he announced, looking back at me. A momentary frown flitted across his face, as if he was unsure of me, but it vanished almost too fast to see.

I supposed he hadn’t really forgotten our strained conversation from the day before, even though he’d put on a good show of it. I played along. “I hope they’re useful,” I said. The chances of the pages holding anything but chart headings and maintenance information were slim, but I still hoped for a break from the “normal” side of this damned investigation.

“I asked him to concentrate on the pages near the end, where the most recent entries were. We’ll see. . . .”

And in the meantime Solis and I would pretend strange things hadn’t happened yesterday and carry on to the home of Walter Ireland to find out what he had to say about his missing daughter.

Ireland, like the Princes, was elderly, and a widower besides. We got lucky in that he was one of those guys whose family was helping out rather than dumping him into a retirement home. His two remaining children were at the house when we arrived, and it appeared we’d interrupted a lively game of poker—the dining room table was spread with cards, chips, and snacks, and the elder Ireland was comfortably parked at one end in a wheelchair that was slightly ratty but lovingly padded with a crazy collection of brocade pillows and clashing blankets.

We’d been met at the door by a woman in her late thirties with black-walnut hair that was unashamedly straight out of a bottle. She introduced herself as Jen and her older brother as Jon and waved at her father as we drew near, saying, “Hey, Dad, what you been up to? The cops are here! Have you been drag racing again?”

Revenant

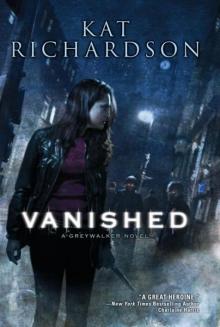

Revenant Vanished

Vanished Labyrinth

Labyrinth Greywalker

Greywalker Seawitch: A Greywalker Novel

Seawitch: A Greywalker Novel Underground (Greywalker, Book 3)

Underground (Greywalker, Book 3) Downpour

Downpour Underground

Underground Possession

Possession Greywalker g-1

Greywalker g-1 Poltergeist (Greywalker, Book 2)

Poltergeist (Greywalker, Book 2) Seawitch g-7

Seawitch g-7 Labyrinth g-5

Labyrinth g-5 Possession g-8

Possession g-8 Downpour g-6

Downpour g-6 Vanished g-4

Vanished g-4 Poltergeist g-2

Poltergeist g-2